The petite performer’s remarkably sweet and strong voice, dusted with just the slightest of childhood lisps, delighted the crowd.

But it was the little mimic’s extraordinary talent for singing her selections in the exact manner of the popular performer she first heard render them that, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, invariably sent otherwise jaded vaudeville crowds into “raptures of delight”.

He was a magician so good, an American pretended to be Chinese to copy him

He was a magician so good, an American pretended to be Chinese to copy him

As the Foo troupe toured, and to placate public demand for more of the performer voted by New York crowds “the most charming child on the boards”, special afternoon shows overseen by Chee Toy’s mother were added.

At these events, crowds of women and children, Chee Toy’s principal audience, came to meet her and receive autographed photos.

A remarkable phenomenon in a country that had, a little over 15 years earlier, passed the China Exclusion Act and where a reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer felt it necessary to inform readers that Chee Toy and her mother were, “contrary to the general occidental idea of Chinese females, an attractive pair”.

A columnist for the Stage section of the Washington Evening Star, writing in January 1900, gave some hint of what lay behind the five-year-old performer’s hold on the American public.

How China became the dominant force in world chess – with help from Asia

How China became the dominant force in world chess – with help from Asia

“The tiny soubrette breathes the perfume of child sweetness about the stage like some dainty bloom from an Asiatic conservatory. She has none of the trite mannerisms of precocity. She is as natural as sunshine and as autocratic as a prima donna.”

Chee Toy remained an overwhelming crowd and media favourite right to the end of the troupe’s wildly successful first US tour, but little did anyone suspect, when the Foo family returned to China in May 1900, it would be more than a decade before a much older and even more formidable Chee Toy returned to America to take vaudeville by storm.

That triumphant return would be enabled by no less than legendary theatre impresario Oscar Hammerstein. Touring Europe in 1912 looking for new acts, Hammerstein encountered Chee Toy and the Foo troupe at the Berlin Opera House.

Seasoned assessor of talent that he was, Hammerstein instantly recognised Foo’s undiminished capacity to pack vaudeville venues back home.

What really struck Hammerstein, however, was what became of the former child star Chee Toy.

The little charmer of the first tour had, through a steady regime of training in both classical Western and traditional Chinese music, transformed herself into a strikingly magnetic adult stage personality, with a marvellously controlled contralto.

Sufficiently entranced, Hammerstein quickly engaged Foo in a generous agreement to headline his vaudeville theatres in the US, and the contract contained a clause laying out the path for Chee Toy to become the theatrical producer’s next diva.

The San Francisco Chronicle trumpeted the novel deal. “Oscar Hammerstein, the famous New York impresario, has reached into the Far East to add to the stage attractions he puts on every year in this country and Europe.

How Chinese keyboard apps could potentially expose everything you type

How Chinese keyboard apps could potentially expose everything you type

“He has picked Chee Toy, the 17-year-old daughter of Ching Ling Foo, one of the most famous Chinese magicians, to be the first opera star from the Orient, and so positive is Hammerstein that she will some day be a wonder that he has staked her to a five-year musical education in Paris.

“At the end of her study, he will launch her upon an operatic career with all the prestige of his name behind her.”

The classical-music-loving Chee Toy was all-in on the deal. Agreement in hand, Hammerstein next undertook the efforts required to get Chee Toy and the Foos past the previously impregnable China Exclusion Act and back into the US.

The Foo troupe had not been absent from the rich American market all these years by choice. Over the past decade US anti-Chinese immigration laws had been repeatedly tightened. As a result, earlier efforts to have them return had failed.

The always innovative Hammerstein – whose great wealth was based on numerous patented manufacturing devices for rolling and wrapping tobacco leaves that he had developed for the burgeoning tobacco industry – faced no such fate.

In quick order a deft lobbying campaign orchestrated by Hammerstein resulted in a pioneering new guaranteed bond methodology to bring Chinese performers into the US.

So it was that in November 1912 the Foo troupe, including Chee Toy, once more graced the shores of “Gold Mountain”.

Nearing 60 but as charismatic as ever, Foo was welcomed back with fulsome praise, and the teenage Chee Toy, proffering a much different skill set, rapidly rivalled him in appeal and press attention.

Her lively performances combined traditional Chinese singing and music with rapid switches to pitch perfect renditions, in fluent English, of songs from the popular new music genre known as ragtime.

A precursor to jazz, ragtime, developed by African-American composers such as Scott Joplin, was, with its jaunty rhythms and bouncing melodies, the perfect musical backdrop for a bustling country in a good mood.

Why the party’s over for Chinese venture capitalists in Silicon Valley

Why the party’s over for Chinese venture capitalists in Silicon Valley

Chee Toy’s renditions of popular ragtime songs “Mississippi Rag” and “Hitchy Koo” proved show-stoppers. Such was her popularity during the 1912 to 1915 American tour that she was often billed and promoted separately from the Foo troupe.

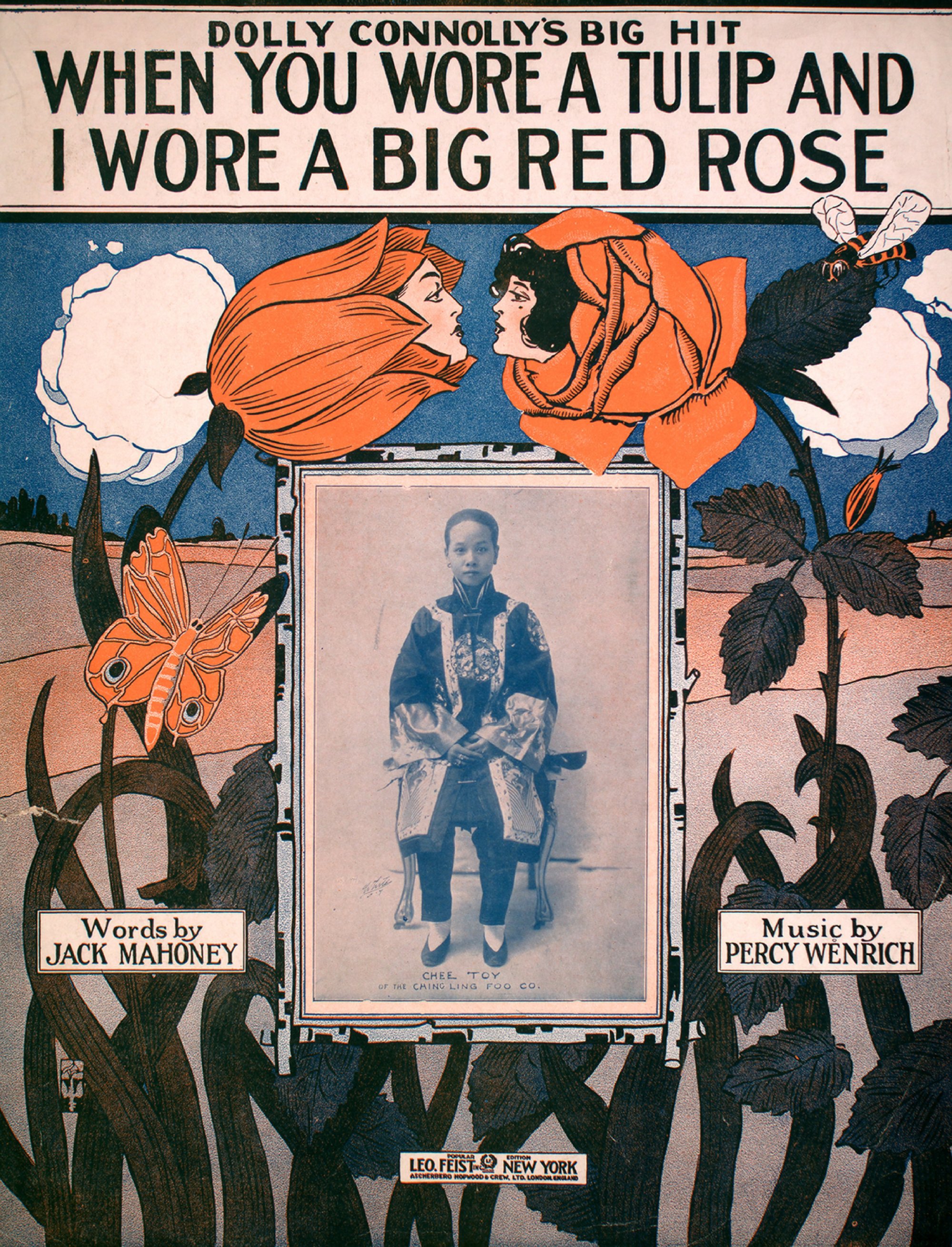

In addition, in an era when the sale of sheet music was a big industry, publishers regularly employed photos of Chee Toy on the covers of their products to increase sales.

The remarkable nature of this young Chinese woman’s success, given the constant stream of Yellow Peril-style “menace of the Mongolian element” news stories and entertainment featuring “ocre-skinned conspirators” inundating the public during this period, was not lost on critics.

One wry comment on the phenomenon came out of New York in late 1913 and was carried across the US wire services. The author first approvingly noted the diminutive Chee Toy’s “touch of an accent” and “thoroughly Parisian shrug of the shoulder” and assessed her as having “enough personality for a second Maude Adams”, who was at the time the most popular and highest paid actress in America.

He then went on to observe of the much discussed Yellow Peril, that it “thus far” seems to have “invaded only vaudeville”, concluding, “In any case, we have made no effort to resist it. How could we when it comes trotting along to ragtime?”

It was during this second tour, the apex of Chee Toy’s fame, that it was finally revealed that she was not, as promoted since 1898, Foo’s daughter.

At that point she was, unbeknown to her adoring public, married to Foo’s husky son and alleged alumnus of Cornell University’s prestigious Chinese student programme, Yee Dee.

Late in the second tour Yee Dee took a role in managing the troupe’s business affairs while sometimes acting as Foo’s right-hand man during the magician’s stage act.

In an interview with Gertrude Price of the Los Angeles Record in 1915, Chee Toy disclosed that both her parents had died when she was only three months old and she had been in show business, which she “loved” along with “the people in it”, since she was three. (Chee Toy’s association with the Foo family from early childhood may have been an example of an old Chinese practice wherein some families took in girls to be raised within the family with the ultimate goal of them marrying their sons.)

This mid-tour revelation might have been felt necessary given the attention the increasingly famous “Musical Marvel of Four Continents” was receiving, including the emergence of an Irish song, “I Married the Daughter of Ching Ling Foo”, and frequent inquiries from an increasingly rambunctious press as to whether Chee Toy would ever consider marrying an American.

The Foo troupe’s summer of 1915 departure from the US was exquisitely timed. Promotions for their last shows jostled on the entertainment pages with ads for the early films of a rising young actor billed as “Charles Chaplin” and D.W. Griffith’s equally groundbreaking and equally problematic film The Clansman (later renamed The Birth of a Nation).

Chee Toy and the Foo Troupe exited American vaudeville at the very point it was overtaken by film.

The record of what happened next in Chee Toy’s life is spotty. The planned post-tour move to Europe for formal training with famed opera coach Jean De Reszke never occurred.

By 1915 the profligate and ageing Hammerstein’s money-losing opera investments had multiplied, and his more commercially shrewd sons finally reined in his high-spending ways.

British Museum’s incredible Chinese history exhibition is a revelation

British Museum’s incredible Chinese history exhibition is a revelation

Perhaps Chee Toy herself, now married, felt compelled by familial responsibilities to defer her much-stated dream of leading a company focused on Western opera. (There were reports in magic circles post the second US tour that she and Yee Dee had had a child.)

Not until the late 1920s do we again see public mention of Chee Toy. A Hongkong Daily Press report in February 1928 provides one of the best accounts of the power Chee Toy still wielded over an audience before whom Chinese performers were no novelty.

“Dressed in rose pink” and framed by a simple stage setting comprised of a black wood table and chairs with a dull yellow background, Chee Toy sang in both Chinese and English in what was described as a “small sweet voice” that “fills the theatre”.

But there was nothing small about the impact the petite one-time aspiring prima donna had on her audience. A perceptive Hong Kong reporter observed there was “something fresh and altogether unusual” about Chee Toy, qualities that first “hushed […] the house to silence then stirred it to a storm of applause”.

Five years later, Chee Toy’s perhaps ill-advised final US tour began with a run at the Chinese pavilion at the 1933 “Century of Progress” Chicago World’s Fair.

As per her first US tour, the fair served both as a visa-granting entry into the US and launching pad for subsequent tours across the country. But vaudeville’s golden era was long past. By 1933, talking pictures dominated what were once vaudeville theatres.

During a 2021 memorabilia auction, a photograph of the ‘Musical Marvel of Four Continents’, estimated to go for a little over US$100, sold for US$12,870

Those owners who still employed live performers often had them perform in rushed, 10-minute opening acts played out as people took their seats before the films began. It was vaudeville’s last gasp in a Depression-era America and it lacked dignity.

At the time, one of the few refuges for the better live acts was the thriving big-city nightclub scene. Major acts could still get lucrative bookings at exclusive venues such as New York’s El Morocco.

These venues seated more than 800 and their entertainment skewed towards the type of dance numbers and chorus girls Chee Toy would have encountered during her stint with the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway.

Gamely adapting to these changes, Chee Toy’s troupe, now rebranded the Ching Ling Foo Jr troupe, and made up mostly of family members of her now second husband, Chinese theatre impresario Paun Yu Jan, played the venues available.

No surprise, then, that the highest-profile gig Chee Toy’s troupe signed on for during this last US tour was as a backup act for the notorious Sally Rand.

A Chinese artist made Tintin less racist, became one of Hergé’s best friends

A Chinese artist made Tintin less racist, became one of Hergé’s best friends

Chee Toy and Rand had crossed paths earlier at the Chicago World’s Fair. Rand, arguably the biggest star to have emerged from the “Century of Progress” event, was a burlesque dancer whose innovation was rapidly deploying ostrich feathers to protect her modesty.

The original fan dancer from Missouri, America’s aptly named “Show Me State”, had earned her fame at the fair by – in what turned out to be an excellent career move – getting arrested for indecency up to four times a day.

Now approaching 40, Chee Toy took her somewhat straitened circumstances in her stride. Wisely sensing a change in mood and tastes she took to the stage selectively, depending on the appropriateness of the venue.

In one instance during a visit to Chicago in November 1933 she sang on live radio for the first time.

However, apart from these rare performances, Chee Toy, “a woman of extraordinary intelligence” as per the Buffalo Evening News, mostly worked backstage managing the troupe with her husband.

This led to some interesting encounters. Beatrice Burgham of the Indianapolis Press came across Chee Toy backstage while looking to provide short “behind the scenes” vignettes.

In one of Chee Toy’s last significant appearances in the American press the journalist describes 1930s Chee Toy as a “busy”, “tiny”, “quiet” “Chinese woman” who once “dreamed of being a prima donna”.

Burgham informed her readers that “instead” she now works backstage with her husband “handing props to a troupe of acrobats, jugglers and magicians”, clutching “a scrapbook of press clippings” telling “stories’’ of her “father’s magical show”.

Happily, that was not the final word on Chee Toy. Because of a current, renewed interest in vaudeville, she is enjoying something of a much-deserved renaissance.

During a 2021 memorabilia auction, a photograph of the “Musical Marvel of Four Continents”, estimated to go for a little over US$100, sold for US$12,870.